Footsteps crossing pavement.

The faint ‘swoosh’ of the imaginary sword of Zorro.

Wind howling and drifting in the night above car horns and urban ambience.

And suddenly, the shadows come alive.

Young eyes fall upon one of them as it splits off from a building and forms into a man making his approach.

A mother reaches for the hand of her son. Dirty fingers clamp around the handle of a shimmering revolver. A father steps forward in defense. A voice of hellish granite asks for trinkets.

Fate calling forth in sorrow.

Two gunshots.

The mother’s screams ring out and up into the brick stone chasms,

carrying up into the skyline above.

Pearls twinkle, bathed in moonlight, striking wet asphalt as blood pools and bodies fall.

A child falls to his knees. The man flees into the shadows once more.

Innocence dies as they die.

There are no words that can be said.

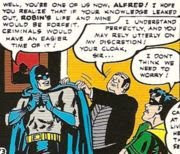

Throughout his literary history, Batman’s adventures, his triumphs and

failures, his enemies and his allies, have all been birthed from a single

catalyst of emotional torment and anguish.

The murders of Dr. Thomas Wayne and Martha Wayne.

It is upon the foundation of their lives being lost that the legend of

Batman has been established in every telling of his origins.

Tragedy is the basis upon which the purpose of Batman’s creation was

forged. It is in this realization that those who have embraced the character

have come to terms with being able to relate to him in spite of the

superficiality of his wealth and social status out of costume. You have never truly lived until you have

suffered, whether it’s the loss of a loved one or a monumental failure, as represented

in the comics by the death of Jason Todd or the paralysis of Barbara Gordon.

Other characters, from Spider-Man and Daredevil to the Punisher, have

followed the same formula.

But none have the momentum or impact of its representation and use in

the world of Batman.

The persona, created by orphaned Bruce Wayne, was done so in the hope

that such an incident would never befall another child ever again; that the

virus of criminality would never plague and infect an undeserving soul,

stripping innocence away needlessly.

There are several results that have stemmed from the murder of Bruce’s

parents; however, there are a nearly equal number of fascinating observations

in the murder itself that represent psychological motivation for the character.

Perhaps the most potent question is the matter of guilt.

Several iterations of the origin’s telling discuss the possibility that

Bruce himself was the indirect result of what happened. In 2005’s “Batman

Begins,” it was Bruce’s inability to cope with his fear of bats that forced him

to seek solace by asking his father to leave the opera.

After the fact, Bruce chooses to condemn himself, blaming their deaths on his cowardice.

In a way, as morbid as it might appear, this could reflect a

coming-of-age tale.

Consider; in the Alan Moore story “For the Man who has everything,” an

alien-creature bonds to Batman, manifesting a hallucination of his inner most

desire, which is to see his parents survive their encounter with the mugger.

Thomas and Martha could be seen as an existential representation of all

that Bruce wants in life and, by extension, all that the readers want in life,

whatever that may be per the individual reader.

To have fear is a natural part of life. But to allow such fear to

control you is to allow it a chance to take that which you covet most away from

you. That could mean something tangible, like a loved one or a job opportunity.

It could also mean something intangible, like self-confidence, peace of mind,

morality, personal fulfillment or purpose.

What you want out of life will be lost if you do not have the courage to take a stand for it.

What you want out of life will be lost if you do not have the courage to take a stand for it.

Bruce seeks to rectify this injustice by becoming Batman and working to ensure that the chance of happiness that was stolen from him by fear isn’t stolen from anyone else.

While pertinent, this is merely speculation. Casting the shadow of

survivor’s guilt onto Batman isn’t easily handled and this is merely on the

principle that we’re talking about a child. Try as he might to consider the

possibility that he could’ve made a difference, Bruce was eight years old.

Generally, no one could ever expect an eight year old boy to take action

against an armed assailant after just witnessing his own parents being gunned

down.

However, this ties into an even bolder forum of discussion.

Is Bruce Wayne insane?

Is the Batman persona a manifestation of that psychological scarring?

Is declaring to purge society of crime a noble goal with justified sacrifice or a hopeless endeavor meant to act more as Bruce’s self-imposed therapy?

It seems unlikely that Batman would need guilt as a sufficient means of motivation. He’s always appeared stronger than that.

Is declaring to purge society of crime a noble goal with justified sacrifice or a hopeless endeavor meant to act more as Bruce’s self-imposed therapy?

It seems unlikely that Batman would need guilt as a sufficient means of motivation. He’s always appeared stronger than that.

The majority of the mythology is built upon the fact that Bruce

willingly chooses the life of Batman. Therefore he’s willingly choosing to

forsake happiness. This suggests what’s stated in “Batman Begins;” that Bruce’s

guilt is outweighed by his anger.

Therefore, it’s less about Wayne feeling guilty for surviving and more about

his feeling angry for simply not having the courage to take action.

This is still self-imposed, but it feels more empowering than

empathetic.

This makes the Batman persona not a means of self-damnation; a crime fighting purgatory of Bruce’s own making...but instead something healing.

This makes the Batman persona not a means of self-damnation; a crime fighting purgatory of Bruce’s own making...but instead something healing.

Redemption on the wings of a bat.

Another interesting point to be made concerning the Wayne murders is

the common piece of iconography in the Batman mythology.

The pilgrimage; a point in time during a narrative, most often the anniversary of their deaths or when his heart hangs most heavy, that Bruce decides to reflect on the catalyst to his becoming Batman through a visit...either to the very spot upon which they were murdered or to the grave where they were put to rest.

Now what I find so fascinating about this is the simple fact that there

are a number of ways the pilgrimage can take place.

Bruce visiting the scene of the murder in daylight.

Batman visiting the scene of the murder at night.

Bruce visiting the grave.

Batman visiting the grave.

The choice to make the pilgrimage may be consistent, but I find that

different elements can be implied or emphasized depending on the manner in

which the character does so.

Personally, I find that the need to visit the site itself only occurs (or perhaps more accurately, SHOULD occur) at a point when the character feels the weight of his promise of avenging their deaths either becoming too much of a burden or becoming lost in focus. This is expertly demonstrated in the “Batman: The Animated Series” episode “I Am The Night,” which sees Batman at a point of vulnerability where he questions the validity of his mission.

Personally, I find that the need to visit the site itself only occurs (or perhaps more accurately, SHOULD occur) at a point when the character feels the weight of his promise of avenging their deaths either becoming too much of a burden or becoming lost in focus. This is expertly demonstrated in the “Batman: The Animated Series” episode “I Am The Night,” which sees Batman at a point of vulnerability where he questions the validity of his mission.

“Every year I come here, I wonder if it should be for the last time. If

I should put the past behind me. Try to lead a normal life.”

This is also showcased in the 2010 Fan Film “Batman: City of Scars;” the fact

that Bruce is visiting the actual site seems to parallel his inner struggle and

self-loathing within the context of that piece.

The site of the murder, given such observation, seems to reflect the more negative aspects of the world Batman inhabits. It is the culmination of tragedy; the epicenter of all the horrible truths and insecurities that Batman confronts on a nightly basis. In such a manner, visiting the site seems to be a bit unhealthy for the character. It’s a place of sadness, a negative energy that unfortunately keeps drawing Batman back.

Some could argue, in an astral sort of understanding, that visiting the

site is proper because it’s a pure representation; Bruce visiting the last spot

where they were alive, feeling the connection frozen in time and tethered to

that piece of concrete. Like the difference between turning to Mecca in prayer

and actually BEING in Mecca.

In juxtaposition, you have the grave and this seems to be given more of

a positive touch.

At the end of the “Batman: The Animated Series” episode “Nothing to Fear,” Bruce visits the grave upon successfully defeating the Scarecrow and overcoming his fear, personified by a ghostly vision of Thomas Wayne, claiming Bruce to be a disgrace to the Wayne family name.

The grave, within context of the episode and Batman’s arc, seems to

represent a need for Bruce to cleanse the memory of his parents after the

dilution Crane’s Fear Toxin attempted to create; as if to say that the grave is

the one true point of connection and anything else is just a derivative.

I think there’s a sense of honor to be found in visiting the grave rather than the site of the murders. The site certainly has more of a gut reaction, but consider the aforementioned idea that the site carries the weight of the tragedy with it.

I think there’s a sense of honor to be found in visiting the grave rather than the site of the murders. The site certainly has more of a gut reaction, but consider the aforementioned idea that the site carries the weight of the tragedy with it.

The grave carries its own share of presence, but I think it’s more

uplifting. As with the end of “Nothing to Fear,” Bruce visits the grave to

reassure himself of the true memory of his father rather than the one conjured

up by the Toxin.

There’s also something more prophetic in the imagery of grave, especially with Batman rather than Bruce. In the 1993 film “Batman: Mask of the Phantasm,” Batman visits the grave in costume and just the image alone is enough to provoke a stimulating reaction. However, Batman visiting the grave is really illogical, seeing how anyone bothering to pay attention could eventually put two and two together and determine Batman’s identity that way (something that actually DOES happen in “Mask of the Phantasm.”)

In the question of Bruce making the pilgrimage in or out of costume, it’s tough.

As stated, visiting the grave in costume is a very big risk to his

identity and, therefore, Batman visiting the site makes the most sense if he’s

going to do so in costume. Being cloaked in the cape and cowl also represents

the popular notion that Bruce Wayne was actually another casualty that

night...and Batman was the orphan that survived and carried on. This could mean

that Batman is actually visiting to symbolically mourn the passing of the Wayne

family. Personally, I’d love to see this scene take place with Batman or Bruce

placing THREE roses in remembrance rather than the traditional two, just to see

what fans would think.

When the pilgrimage is done out of costume as Bruce, it seems to reflect on the idea that him as he once was still exists...but only when he visits. In “City of Scars,” this is handled visually with a pair of sunglasses, which are taken off upon his arrival and placed back on as he departs.

He drops his guard. He becomes vulnerable. Visiting the site of the murder, he becomes that little eight year old boy once more...if only for a moment...before slipping back into the foppish, playboy public ‘Bruce Wayne’ role that he has to fill.

Whatever speculation or aspect exists, there’s no denying the impact of

the Wayne murders.

There would be no Batman without them, in context.

We’ve all endured the pain of loss in one form or another.

It’s a universal constant and, I think, one of the key elements to

Batman’s longevity and success.

There’s no sense in trying to relate to a hero unless there is

something fundamental that everyone can identify with.

Given his global popularity, it seems evident that the mindless death

of family and the stripping of innocence is such a fundamental.

The birth of Batman grew out of tragic origins.

It represents the idea that out of such tragedy, we can learn to cope

and overcome. We can learn to evolve and take the pain, transforming it into

something hopeful and powerful. We can fight on and endure heartbreak. We can

honor the memory, take it with us and allow it to guide us.

Batman is the spirit of the human soul’s will to stay the course.

Tragedy is everlasting. It will forever remain a constant and inescapable threat; the price of being human.

Tragedy is everlasting. It will forever remain a constant and inescapable threat; the price of being human.

But life without tragedy is a life half-lived.

Without it, we wouldn’t have the means to find the strength within.

The strength to go on.

To aspire and to live.